Lilium philadelphicum

Sp. Pl. ed. 2, 1: 435. 1762.

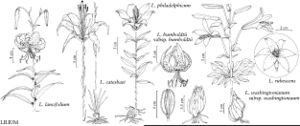

Bulbs chunky, 1.6–2.9 × 2.2–4.7 cm, 0.6–1.1 times taller than long, 2(–4) years’ growth visible; scales 1–2-segmented, longest 1.2–2.2 cm; stem roots present or absent. Stems to 1.2 m, glaucous. Buds rounded in cross section. Leaves scattered, or mostly scattered with at least 1 distal whorl, or in 1–5 whorls or partial whorls, 3–11 leaves per whorl, ± horizontal and drooping at tips, or ascending in sun, 2.9–10.2 × 0.3–2.3 cm, 3.5–18 times longer than wide; blade narrowly elliptic, sometimes linear, elliptic, or oblanceolate, margins not undulate, apex acute or barely acuminate; veins and margins ± smooth abaxially. Inflorescences umbellate, 1–3(–6)-flowered. Flowers erect, not fragrant; perianth widely campanulate; sepals and petals somewhat recurved 1/4–2/5 along length from base, red-orange or red-magenta, sometimes pale orange, pure red, or rarely yellow, distinctly clawed, apex often widely acute, rarely obtuse, nectar guides above claws yellow to orange and spotted maroon, more pronounced on sepals; sepals not ridged abaxially, 4.9–8.2 × 1.6–2.6 cm; petals 4.5–7.7 × 2–3.2 cm; stamens strongly exserted; filaments ± parallel to style, barely spreading, diverging 0°–8° from axis, ± same color as sepals and petals; anthers dull maroon, 0.5–1.2 cm; pollen variously colored dark orange, brown, brown-yellow, or yellow; pistil 5–8 cm; ovary 1.3–3.2 cm; style ± same color as sepals and petals; pedicel 2.5–10.5 cm. Capsules 2.2–7.7 × 1–1.8 cm, 3–4.8 times longer than wide. Seeds not counted. 2n = 24.

Phenology: Flowering late spring–summer (late May–Aug), earliest in s Appalachians, latest in n Rocky Mountains.

Habitat: Tallgrass prairies, open woods, thickets, roadsides, powerlines, e balds, barrens, dunes, and heathlands, w mountain meadows

Elevation: 0–2700 m

Distribution

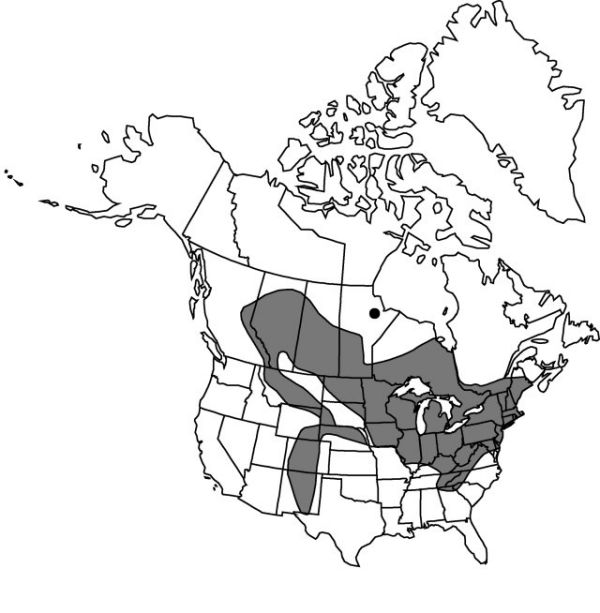

Alta., B.C., Man., Ont., Que., Sask., Colo., Conn., Del., D.C., Ga., Ill., Ind., Iowa, Ky., Maine, Md., Mass., Mich., Minn., Mo., Mont., Nebr., N.H., N.J., N.Mex., N.Y., N.C., N.Dak., Ohio, Pa., R.I., S.C., S.Dak., Tenn., Tex., Vt., Va., W.Va., Wis., Wyo.

Discussion

Lilium philadelphicum is the widest ranging of our true lilies. Rather common in high meadows of the mountain west and some intact tallgrass prairies of the Great Plains and adjacent corn belt, it is decidedly rare to the east in lower midwestern prairies of the United States and in the southern Appalachians, where it is protected by several states. It has declined rapidly in the northeastern United States as prairies disappear and white-tailed deer [Odocoileus virginianus (Zimmermann), family Cervidae] continue to increase in number. In many places in the eastern U.S., the most reliable habitats are powerline right of ways that are maintained by brush-clearing.

The northernmost populations are introduced along the railway from Gillam to Churchill on Hudson Bay (H. J. Scoggan 1978–1979, part 2), though the wood lily is native and widespread farther south in Manitoba. Reports from Arkansas cannot be verified, and an 1869 D. E. Palmer specimen with the locality given as Arizona was probably collected in New Mexico or Colorado. Surprisingly, there are no known records for the area extending from southwestern Iowa to southeastern Alberta.

Lilium philadelphicum is highly variable in stature, leaf size and arrangement, flower color, and fruit length, and it is this variation that has accounted for the proliferation of names—only a few of which are cited above—applied to this taxon. Of these, only one remains in general use. Variety andinum has come to include usually western plants of smaller stature that have long capsules (4–8 cm vs. 2.5–3.5 cm in var. philadelphicum) and are characterized by scattered leaves usually topped by a single whorl (E. T. Wherry 1946). The typical habitat for these plants is the low grassy vegetation found in tall- and midgrass prairies and mountain meadows. The usually accepted break between this entity and var. philadelphicum runs north to south along the eastern border of Ohio (E. L. Braun 1967), and thus northeastern and Appalachian plants are normally assigned to the nominate variety. These are more often plants of open woods or thickets, though they do occur in low vegetation, including Appalachian balds and eastern prairies. Field studies show that these specimens tend to be large, with a mean stem height of 81 cm, compared to 48 cm in western plants. Leaf arrangement consists of 2–5 whorls of 3 or more leaves (averaging 3.8 whorls) as opposed to the more western plants typically assigned to var. andinum, which display 0–5 whorls, averaging 1.3 whorls per plant. Leaves are also longer and wider in these eastern and Appalachian plants and average 6.9 cm long (3.8–10.2 cm) by 1.3 cm wide (0.7–2.3 cm), compared with 5.1 cm long (2.9–7.7 cm) by 0.6 cm wide (0.3–1.4 cm) in plants sampled from western Ohio and Colorado. Other individuals disrupt this pattern. Plants from Nantucket, Massachusetts (presumably of low heath or grassland), fall within the range of variation of mountain plants from Colorado. These dwarf individuals have small flowers and short (ca. 4 cm), very narrow (ca. 0.4 cm) leaves, albeit mostly in whorls. Equally significant are massive plants of moist woods in Colorado with fully whorled, long (to 9.2 cm), and rather wide leaves (to 1.3 cm). Other Colorado plants are vegetatively indistinguishable from certain Connecticut material.

Somewhat surprisingly, given its relatively modest stature, the wood lily has the longest capsules of any Lilium in North America. The largest-fruited individuals seen come from the Appalachians, not from populations otherwise assignable to the purportedly long-fruited var. andinum. Fruit lengths average larger in these robust Kentucky plants (mean 6.2 cm, range 5.1–7.7) than in western Ohio plants (mean 4.3 cm, range 3–5.8). Plants from Vermont that are clearly assignable to var. philadelphicum on the basis of leaf size and arrangement have capsules of comparable size to those in western Ohio (mean 4.1 cm, range 3.1–5.3).

Therefore, it appears that local environment governs vegetative and fruit morphology to a great degree in Lilium philadelphicum, and in many cases overwhelms the presumed effect of genotype and the broad geographical patterns. Western plants from typically eastern habitats (moist woodlands) resemble eastern plants, and eastern plants from typically more western habitats (low prairie or heath) resemble western plants. The characters invoked to support the var. andinum—especially capsule length—vary continuously and somewhat independently. The status of var. andinum is unsettled and it is not accorded formal recognition here.

Lilium philadelphicum is pollinated by large swallowtail butterflies, in the west by the pale swallowtail (Papilio eurymedon Lucas, family Papilionidae) and western tiger swallowtail (P. rutulus Lucas), in the east by the eastern tiger swallowtail (P. glaucus Linnaeus; E. M. Barrows 1979) and undoubtedly most of the other species resident in its wide range. Hummingbirds occasionally visit the flowers but are unlikely to be equally effective pollinators due to a flower morphology that forces butterfly forewings to contact reproductive structures but probably allows birds ready nectar access without such contact.

The wood lily is the floral emblem of Saskatchewan.

The Cree, Meskwaki, and Blackfoot used Lilium philadelphicum bulbs as food, while other tribes used bulbs medicinally and in witchcraft (D. E. Moerman 1986). The Malecite mixed the roots with those of Rubus species and staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina Linnaeus) to treat coughs and fevers. The Chippewa made a poultice that was applied to dog bites and caused the dog’s fangs to drop out. The Iroquois made a decoction of the whole plant to shed the placenta after childbirth, women used a decoction of the roots as a wash if the husband was unfaithful, and the whole plant was used as a romantic aid: if sun-dried plants twisted together, they signified a wife’s infidelity.

Selected References

None.