Difference between revisions of "Phytolacca americana"

Sp. Pl. 1: 441. 1753.

FNA>Volume Importer |

FNA>Volume Importer |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

|distribution=North America;introduced in Europe. | |distribution=North America;introduced in Europe. | ||

|discussion=<p>Varieties 2 (2 in the flora).</p><!-- | |discussion=<p>Varieties 2 (2 in the flora).</p><!-- | ||

| − | --><p>The infraspecific taxonomy of Phytolacca americana has been disputed since J. K. Small (1905) recognized P. rigida as distinct from P. americana on the basis of its “permanently erect panicles” [sic] and “pedicels…much shorter than the diameter of the berries.” J. W. Hardin (1964b) separated P. rigida from P. americana by the length of the raceme (2–12 cm in P. rigida, 5–30 cm in P. americana) and the thickness and diameter of the xylem center of the peduncle (70% greater thickness in P. rigida, 17% greater diameter in P. americana), but he found no discontinuities in any feature. J. W. Nowicke (1968) and J. D. Sauer (1952), among others, treated P. rigida as a synonym of P. americana. Most recently, D. B. Caulkins and R. Wyatt (1990) recognized P. rigida as a variety of P. americana.</p><!-- | + | --><p>The infraspecific taxonomy of <i>Phytolacca americana</i> has been disputed since J. K. Small (1905) recognized <i>P. rigida</i> as distinct from <i>P. americana</i> on the basis of its “permanently erect panicles” [sic] and “pedicels…much shorter than the diameter of the berries.” J. W. Hardin (1964b) separated <i>P. rigida</i> from <i>P. americana</i> by the length of the raceme (2–12 cm in <i>P. rigida</i>, 5–30 cm in <i>P. americana</i>) and the thickness and diameter of the xylem center of the peduncle (70% greater thickness in <i>P. rigida</i>, 17% greater diameter in <i>P. americana</i>), but he found no discontinuities in any feature. J. W. Nowicke (1968) and J. D. Sauer (1952), among others, treated <i>P. rigida</i> as a synonym of <i>P. americana</i>. Most recently, D. B. Caulkins and R. Wyatt (1990) recognized <i>P. rigida</i> as a variety of <i>P. americana</i>.</p><!-- |

| − | --><p>The varieties are not always clearly distinct. Some specimens combine the erect inflorescences of var. rigida with the long pedicels of var. americana. Such intermediate plants can be seen as far north as coastal Delaware, sometimes growing with var. americana.</p><!-- | + | --><p>The varieties are not always clearly distinct. Some specimens combine the erect inflorescences of <i></i>var.<i> rigida</i> with the long pedicels of <i></i>var.<i> americana</i>. Such intermediate plants can be seen as far north as coastal Delaware, sometimes growing with <i></i>var.<i> americana</i>.</p><!-- |

| − | --><p>Collectors of Phytolacca americana should record carefully whether the inflorescences are erect, drooping, or intermediate between the extremes.</p><!-- | + | --><p>Collectors of <i>Phytolacca americana</i> should record carefully whether the inflorescences are erect, drooping, or intermediate between the extremes.</p><!-- |

| − | --><p>The fruits and seeds of Phytolacca americana are eaten and disseminated by birds and, probably, mammals. They are said to be an important source of food for mourning doves (A. C. Martin et al. 1951).</p><!-- | + | --><p>The fruits and seeds of <i>Phytolacca americana</i> are eaten and disseminated by birds and, probably, mammals. They are said to be an important source of food for mourning doves (A. C. Martin et al. 1951).</p><!-- |

| − | --><p>Phytolacca americana is well known to herbalists, cell biologists, and toxicologists. According to some accounts, its young leaves, after being boiled in two waters (the first being discarded) to deactivate toxins, are edible, even being available canned (they pose no culinary threat to spinach). Young shoots are eaten as a substitute for asparagus. Ripe berries were used to color wine and are eaten (cooked) in pies. Poke is used as an emetic, a purgative, a suppurative, a spring tonic, and a treatment for various skin maladies, especially hemorrhoids.</p><!-- | + | --><p><i>Phytolacca americana</i> is well known to herbalists, cell biologists, and toxicologists. According to some accounts, its young leaves, after being boiled in two waters (the first being discarded) to deactivate toxins, are edible, even being available canned (they pose no culinary threat to spinach). Young shoots are eaten as a substitute for asparagus. Ripe berries were used to color wine and are eaten (cooked) in pies. Poke is used as an emetic, a purgative, a suppurative, a spring tonic, and a treatment for various skin maladies, especially hemorrhoids.</p><!-- |

| − | --><p>Pokeweed mitogen is a mixture of glycoprotein lectins that are powerful immune stimulants, promoting T- and B-lymphocyte proliferation and increased immunoglobulin levels. “Accidental exposure to juices from Phytolacca americana via ingestion, breaks in the skin, and the conjunctiva has brought about hematological changes in numerous people, including researchers studying this species” (G. K. Rogers 1985). Poke antiviral proteins are of great interest for their broad, potent antiviral (including Human Immunodeficiency Virus) and antifungal properties (P. Wang et al. 1998). Saponins found in P. americana and P. dodecandra are lethal to the molluscan intermediate host of schistosomiasis (J. M. Pezzuto et al. 1984). The toxic compounds in P. americana are phytolaccatoxin and related triterpene saponins, the alkaloid phytolaccin, various histamines, and oxalic acid. When ingested, the roots, leaves, and fruits may poison animals, including Homo sapiens. Symptoms of poke poisoning include sweating, burning of the mouth and throat, severe gastritis, vomiting, bloody diarrhea, blurred vision, elevated white-blood-cell counts, unconsciousness, and, rarely, death.</p><!-- | + | --><p>Pokeweed mitogen is a mixture of glycoprotein lectins that are powerful immune stimulants, promoting T- and B-lymphocyte proliferation and increased immunoglobulin levels. “Accidental exposure to juices from <i>Phytolacca americana</i> via ingestion, breaks in the skin, and the conjunctiva has brought about hematological changes in numerous people, including researchers studying this species” (G. K. Rogers 1985). Poke antiviral proteins are of great interest for their broad, potent antiviral (including Human Immunodeficiency Virus) and antifungal properties (P. Wang et al. 1998). Saponins found in <i>P. americana</i> and <i>P. dodecandra</i> are lethal to the molluscan intermediate host of schistosomiasis (J. M. Pezzuto et al. 1984). The toxic compounds in <i>P. americana</i> are phytolaccatoxin and related triterpene saponins, the alkaloid phytolaccin, various histamines, and oxalic acid. When ingested, the roots, leaves, and fruits may poison animals, including Homo sapiens. Symptoms of poke poisoning include sweating, burning of the mouth and throat, severe gastritis, vomiting, bloody diarrhea, blurred vision, elevated white-blood-cell counts, unconsciousness, and, rarely, death.</p><!-- |

--><p>“Poke” is thought to come from “pocan” or “puccoon,” probably from the Algonquin term for a plant that contains dye.</p> | --><p>“Poke” is thought to come from “pocan” or “puccoon,” probably from the Algonquin term for a plant that contains dye.</p> | ||

|tables= | |tables= | ||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

|publication year=1753 | |publication year=1753 | ||

|special status= | |special status= | ||

| − | |source xml=https://jpend@bitbucket.org/aafc-mbb/fna-data-curation.git/src/ | + | |source xml=https://jpend@bitbucket.org/aafc-mbb/fna-data-curation.git/src/8f726806613d60c220dc4493de13607dd3150896/coarse_grained_fna_xml/V4/V4_8.xml |

|genus=Phytolacca | |genus=Phytolacca | ||

|species=Phytolacca americana | |species=Phytolacca americana | ||

Revision as of 17:31, 18 September 2019

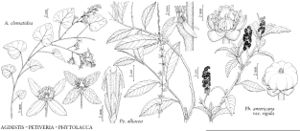

Plants to 3(–7) m. Leaves: petiole 1–6 cm; blade lanceolate to ovate, to 35 × 18 cm, base rounded to cordate, apex acuminate. Racemes open, proximalmost pedicels sometimes bearing 2–few flowers, erect to drooping, 6–30 cm; peduncle to 15 cm; pedicel 3–13 mm. Flowers: sepals 5, white or greenish white to pinkish or purplish, ovate to suborbiculate, equal to subequal, 2.5–3.3 mm; stamens (9–)10(–12) in 1 whorl; carpels 6–12, connate at least in proximal 1/2; ovary 6–12-loculed. Berries purple-black, 6–11 mm diam. Seeds black, lenticular, 3 mm, shiny. 2n = 36.

Distribution

North America, introduced in Europe.

Discussion

Varieties 2 (2 in the flora).

The infraspecific taxonomy of Phytolacca americana has been disputed since J. K. Small (1905) recognized P. rigida as distinct from P. americana on the basis of its “permanently erect panicles” [sic] and “pedicels…much shorter than the diameter of the berries.” J. W. Hardin (1964b) separated P. rigida from P. americana by the length of the raceme (2–12 cm in P. rigida, 5–30 cm in P. americana) and the thickness and diameter of the xylem center of the peduncle (70% greater thickness in P. rigida, 17% greater diameter in P. americana), but he found no discontinuities in any feature. J. W. Nowicke (1968) and J. D. Sauer (1952), among others, treated P. rigida as a synonym of P. americana. Most recently, D. B. Caulkins and R. Wyatt (1990) recognized P. rigida as a variety of P. americana.

The varieties are not always clearly distinct. Some specimens combine the erect inflorescences of var. rigida with the long pedicels of var. americana. Such intermediate plants can be seen as far north as coastal Delaware, sometimes growing with var. americana.

Collectors of Phytolacca americana should record carefully whether the inflorescences are erect, drooping, or intermediate between the extremes.

The fruits and seeds of Phytolacca americana are eaten and disseminated by birds and, probably, mammals. They are said to be an important source of food for mourning doves (A. C. Martin et al. 1951).

Phytolacca americana is well known to herbalists, cell biologists, and toxicologists. According to some accounts, its young leaves, after being boiled in two waters (the first being discarded) to deactivate toxins, are edible, even being available canned (they pose no culinary threat to spinach). Young shoots are eaten as a substitute for asparagus. Ripe berries were used to color wine and are eaten (cooked) in pies. Poke is used as an emetic, a purgative, a suppurative, a spring tonic, and a treatment for various skin maladies, especially hemorrhoids.

Pokeweed mitogen is a mixture of glycoprotein lectins that are powerful immune stimulants, promoting T- and B-lymphocyte proliferation and increased immunoglobulin levels. “Accidental exposure to juices from Phytolacca americana via ingestion, breaks in the skin, and the conjunctiva has brought about hematological changes in numerous people, including researchers studying this species” (G. K. Rogers 1985). Poke antiviral proteins are of great interest for their broad, potent antiviral (including Human Immunodeficiency Virus) and antifungal properties (P. Wang et al. 1998). Saponins found in P. americana and P. dodecandra are lethal to the molluscan intermediate host of schistosomiasis (J. M. Pezzuto et al. 1984). The toxic compounds in P. americana are phytolaccatoxin and related triterpene saponins, the alkaloid phytolaccin, various histamines, and oxalic acid. When ingested, the roots, leaves, and fruits may poison animals, including Homo sapiens. Symptoms of poke poisoning include sweating, burning of the mouth and throat, severe gastritis, vomiting, bloody diarrhea, blurred vision, elevated white-blood-cell counts, unconsciousness, and, rarely, death.

“Poke” is thought to come from “pocan” or “puccoon,” probably from the Algonquin term for a plant that contains dye.

Selected References

Key

| 1 | Pedicels longer than 6 mm in fruit, longer than berries; racemes (10-)12-30 cm (excluding peduncles), divergent or usually drooping; various habitats, widespread. | Phytolacca americana var. americana |

| 1 | Pedicels shorter than 6(-7) mm in fruit, shorter than berries; racemes 6-9(-13.5) cm, erect; e coastal United States, North Carolina and Vir- ginia to Texas. | Phytolacca americana var. rigida |