Difference between revisions of "Larrea tridentata"

Contr. U.S. Natl. Herb. 4: 75. 1893.

FNA>Volume Importer |

imported>Volume Importer |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

}}{{Treatment/ID/Special_status | }}{{Treatment/ID/Special_status | ||

|code=F | |code=F | ||

| − | |label= | + | |label=Illustrated |

}} | }} | ||

| − | |basionyms={{Treatment/ID/ | + | |basionyms={{Treatment/ID/Basionym |

|name=Zygophyllum tridentatum | |name=Zygophyllum tridentatum | ||

| − | |authority=de Candolle in A. P. de Candolle and A. L. P. P. de Candolle | + | |authority=de Candolle |

| + | |rank=species | ||

| + | |publication_title=in A. P. de Candolle and A. L. P. P. de Candolle, Prodr. | ||

| + | |publication_place=1: 706. 1824 | ||

}} | }} | ||

|synonyms={{Treatment/ID/Synonym | |synonyms={{Treatment/ID/Synonym | ||

|name=Larrea divaricata var. arenaria | |name=Larrea divaricata var. arenaria | ||

|authority=(L. D. Benson) Felger | |authority=(L. D. Benson) Felger | ||

| − | }}{{Treatment/ID/Synonym | + | |rank=variety |

| + | }} {{Treatment/ID/Synonym | ||

|name=L. divaricata subsp. tridentat | |name=L. divaricata subsp. tridentat | ||

|authority=(de Candolle) Felger & C. H. Lowe | |authority=(de Candolle) Felger & C. H. Lowe | ||

| − | }}{{Treatment/ID/Synonym | + | |rank=subspecies |

| + | }} {{Treatment/ID/Synonym | ||

|name=L. glutinosa | |name=L. glutinosa | ||

|authority=Engelmann | |authority=Engelmann | ||

| − | }}{{Treatment/ID/Synonym | + | |rank=species |

| + | }} {{Treatment/ID/Synonym | ||

|name=L. tridentata var. arenaria | |name=L. tridentata var. arenaria | ||

|authority=L. D. Benson | |authority=L. D. Benson | ||

| − | }}{{Treatment/ID/Synonym | + | |rank=variety |

| + | }} {{Treatment/ID/Synonym | ||

|name=L. tridentata var. glutinosa | |name=L. tridentata var. glutinosa | ||

|authority=Jepson | |authority=Jepson | ||

| + | |rank=variety | ||

}} | }} | ||

|hierarchy=Zygophyllaceae;Larrea;Larrea tridentata | |hierarchy=Zygophyllaceae;Larrea;Larrea tridentata | ||

| Line 49: | Line 57: | ||

|elevation=-50–1700 m. | |elevation=-50–1700 m. | ||

|distribution=Ariz.;Calif.;Nev.;N.Mex.;Tex.;Utah;Mexico. | |distribution=Ariz.;Calif.;Nev.;N.Mex.;Tex.;Utah;Mexico. | ||

| − | |discussion=<p>Larrea tridentata is the dominant shrub in the lower elevations of the Chihuahuan, Mojave, and Sonoran deserts.</p><!-- | + | |discussion=<p><i>Larrea tridentata</i> is the dominant shrub in the lower elevations of the Chihuahuan, Mojave, and Sonoran deserts.</p><!-- |

| − | --><p>There has been much controversy as to whether North American Larrea is a separate species from the diploid South American L. divaricata Cavanilles (2n = 26), and it has been called L. divaricata subsp. tridentata. However, morphologic (D. M. Porter 1963) and molecular (V. V. Lia et al. 2001) data confirm that they are closely related, but separate, species. The presence of three chromosome races in the three warm desert regions of North America (Chihuahuan, diploid, 2n = 26; Sonoran, tetraploid, 2n = 52; Mojave, hexaploid, 2n = 78) has led to speculation on recognizing three subspecific taxa in L. tridentata. However, the overlapping of chromosome races in southeastern California and central and western Arizona (T. W. Yang 1970; R. G. Laport et al. 2012), and the presence of all three races in Baja California (R. S. Felger 2000), plus the lack of morphologic differentiation between them, argue against doing so.</p><!-- | + | --><p>There has been much controversy as to whether North American <i>Larrea</i> is a separate species from the diploid South American <i>L. divaricata</i> Cavanilles (2n = 26), and it has been called <i>L. divaricata</i> <i></i>subsp.<i> tridentata</i>. However, morphologic (D. M. Porter 1963) and molecular (V. V. Lia et al. 2001) data confirm that they are closely related, but separate, species. The presence of three chromosome races in the three warm desert regions of North America (Chihuahuan, diploid, 2n = 26; Sonoran, tetraploid, 2n = 52; Mojave, hexaploid, 2n = 78) has led to speculation on recognizing three subspecific taxa in <i>L. tridentata</i>. However, the overlapping of chromosome races in southeastern California and central and western Arizona (T. W. Yang 1970; R. G. Laport et al. 2012), and the presence of all three races in Baja California (R. S. Felger 2000), plus the lack of morphologic differentiation between them, argue against doing so.</p><!-- |

| − | --><p>Populations of slender, upright individuals growing on sand dunes in northeastern Baja California, northwestern Sonora, and southeastern California (Imperial County) have been called Larrea tridentata var. arenaria (L. divaricata var. arenaria) (R. S. Felger 2000). The California plants are tetraploid and in a few sites are sympatric with hexaploid individuals; they represent a dune-adapted ecotype (R. G. Laport et al. 2012).</p><!-- | + | --><p>Populations of slender, upright individuals growing on sand dunes in northeastern Baja California, northwestern Sonora, and southeastern California (Imperial County) have been called <i>Larrea tridentata</i> <i></i>var.<i> arenaria</i> (<i>L. divaricata</i> <i></i>var.<i> arenaria</i>) (R. S. Felger 2000). The California plants are tetraploid and in a few sites are sympatric with hexaploid individuals; they represent a dune-adapted ecotype (R. G. Laport et al. 2012).</p><!-- |

| − | --><p>Black banding at the nodes of Larrea tridentata is caused by resin secreted by glands on the inner surfaces of the stipules. Surfaces of younger parts are resinous and sticky; the odoriferous resins give it the common name, creosote bush. The plant has been widely used medicinally by Native Americans (R. S. Felger 2007). Nordihydroguaiaretic acid is abundant in L. tridentata resins and has been used as an antioxidant in foods, pharmaceuticals, and industrial materials (T. J. Mabry et al. 1977).</p><!-- | + | --><p>Black banding at the nodes of <i>Larrea tridentata</i> is caused by resin secreted by glands on the inner surfaces of the stipules. Surfaces of younger parts are resinous and sticky; the odoriferous resins give it the common name, creosote bush. The plant has been widely used medicinally by Native Americans (R. S. Felger 2007). Nordihydroguaiaretic acid is abundant in <i>L. tridentata</i> resins and has been used as an antioxidant in foods, pharmaceuticals, and industrial materials (T. J. Mabry et al. 1977).</p><!-- |

| − | --><p>Clones of Larrea tridentata in the Mojave Desert in San Bernardino County, California, have been estimated to be about 11,700 years old based on present growth rates (F. C. Vasek 1980). However, the oldest dated Larrea pollen from nearby packrat middens is no more than 5,880 years old, so the clones may be younger than thought (R. S. Felger et al. 2012). Fossil L. tridentata wood from Yuma County, Arizona, has been radiocarbon dated as 10,850 plus or minus 500 years old (P. V. Wells and J. H. Hunziker 1977). Fossil leaves from Yuma County have been dated to 18,700 plus or minus 1050 years (T. R. Van Devender 1990), while pollen from Inyo County, California lake sediments has been dated to 47,000 (Owens Lake) (W. S. Woolfenden 1996) and 109,000 years old (Badwater) (N. E. Bader 1999). The species, or its progenitor, is estimated to have dispersed from South America between about 0.5 and 8.4 million years ago (V. V. Lia et al. 2001; R. G. Laport et al. 2012).</p> | + | --><p>Clones of <i>Larrea tridentata</i> in the Mojave Desert in San Bernardino County, California, have been estimated to be about 11,700 years old based on present growth rates (F. C. Vasek 1980). However, the oldest dated <i>Larrea</i> pollen from nearby packrat middens is no more than 5,880 years old, so the clones may be younger than thought (R. S. Felger et al. 2012). Fossil <i>L. tridentata</i> wood from Yuma County, Arizona, has been radiocarbon dated as 10,850 plus or minus 500 years old (P. V. Wells and J. H. Hunziker 1977). Fossil leaves from Yuma County have been dated to 18,700 plus or minus 1050 years (T. R. Van Devender 1990), while pollen from Inyo County, California lake sediments has been dated to 47,000 (Owens Lake) (W. S. Woolfenden 1996) and 109,000 years old (Badwater) (N. E. Bader 1999). The species, or its progenitor, is estimated to have dispersed from South America between about 0.5 and 8.4 million years ago (V. V. Lia et al. 2001; R. G. Laport et al. 2012).</p> |

|tables= | |tables= | ||

|references= | |references= | ||

| Line 62: | Line 70: | ||

-->{{#Taxon: | -->{{#Taxon: | ||

name=Larrea tridentata | name=Larrea tridentata | ||

| − | |||

|authority=(de Candolle) Coville | |authority=(de Candolle) Coville | ||

|rank=species | |rank=species | ||

| Line 76: | Line 83: | ||

|publication title=Contr. U.S. Natl. Herb. | |publication title=Contr. U.S. Natl. Herb. | ||

|publication year=1893 | |publication year=1893 | ||

| − | |special status=Weedy; | + | |special status=Weedy;Illustrated |

| − | |source xml=https:// | + | |source xml=https://bitbucket.org/aafc-mbb/fna-data-curation/src/2e0870ddd59836b60bcf96646a41e87ea5a5943a/coarse_grained_fna_xml/V12/V12_765.xml |

|genus=Larrea | |genus=Larrea | ||

|species=Larrea tridentata | |species=Larrea tridentata | ||

Latest revision as of 19:17, 5 November 2020

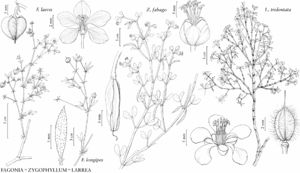

Shrubs, divaricately-branched, multistemmed, strong-scented, resinous. Stems reddish when young, becoming gray or black, black-banded, slender. Leaves: stipules spreading, not clasping stem, 1–4 mm, fleshy, resinous; petiole to 2 mm; leaflets green to olive brown, 4–18 × 1–8.5 mm, inequilateral, coriaceous, surfaces glutinous; awn between leaflets deciduous, to 2 mm. Pedicels 3–12 mm, 4–13 mm in fruit. Flowers to 3 cm diam.; sepals ovoid, 5–8 × 3–4.5 mm, appressed-pubescent; petals twisted at claw and appearing propellerlike, 7–11 × 2.5–5.5 mm, claw brownish; stamens 5–9 mm, filaments 4–8 mm, basal scales 2–8 × to 3 mm, 1/2 to as long as filaments; ovary 2–5 mm, stalk 1 mm, densely hairy; style cylindric, 4–6 mm. Schizocarps 4.5 mm diam., pilose-woolly, hairs white, turning reddish brown with age. Seeds 4–5 mm. 2n = 26, 52, 78.

Phenology: Flowering year-round, following rains.

Habitat: Creosote-bush scrub.

Elevation: -50–1700 m.

Distribution

Ariz., Calif., Nev., N.Mex., Tex., Utah, Mexico.

Discussion

Larrea tridentata is the dominant shrub in the lower elevations of the Chihuahuan, Mojave, and Sonoran deserts.

There has been much controversy as to whether North American Larrea is a separate species from the diploid South American L. divaricata Cavanilles (2n = 26), and it has been called L. divaricata subsp. tridentata. However, morphologic (D. M. Porter 1963) and molecular (V. V. Lia et al. 2001) data confirm that they are closely related, but separate, species. The presence of three chromosome races in the three warm desert regions of North America (Chihuahuan, diploid, 2n = 26; Sonoran, tetraploid, 2n = 52; Mojave, hexaploid, 2n = 78) has led to speculation on recognizing three subspecific taxa in L. tridentata. However, the overlapping of chromosome races in southeastern California and central and western Arizona (T. W. Yang 1970; R. G. Laport et al. 2012), and the presence of all three races in Baja California (R. S. Felger 2000), plus the lack of morphologic differentiation between them, argue against doing so.

Populations of slender, upright individuals growing on sand dunes in northeastern Baja California, northwestern Sonora, and southeastern California (Imperial County) have been called Larrea tridentata var. arenaria (L. divaricata var. arenaria) (R. S. Felger 2000). The California plants are tetraploid and in a few sites are sympatric with hexaploid individuals; they represent a dune-adapted ecotype (R. G. Laport et al. 2012).

Black banding at the nodes of Larrea tridentata is caused by resin secreted by glands on the inner surfaces of the stipules. Surfaces of younger parts are resinous and sticky; the odoriferous resins give it the common name, creosote bush. The plant has been widely used medicinally by Native Americans (R. S. Felger 2007). Nordihydroguaiaretic acid is abundant in L. tridentata resins and has been used as an antioxidant in foods, pharmaceuticals, and industrial materials (T. J. Mabry et al. 1977).

Clones of Larrea tridentata in the Mojave Desert in San Bernardino County, California, have been estimated to be about 11,700 years old based on present growth rates (F. C. Vasek 1980). However, the oldest dated Larrea pollen from nearby packrat middens is no more than 5,880 years old, so the clones may be younger than thought (R. S. Felger et al. 2012). Fossil L. tridentata wood from Yuma County, Arizona, has been radiocarbon dated as 10,850 plus or minus 500 years old (P. V. Wells and J. H. Hunziker 1977). Fossil leaves from Yuma County have been dated to 18,700 plus or minus 1050 years (T. R. Van Devender 1990), while pollen from Inyo County, California lake sediments has been dated to 47,000 (Owens Lake) (W. S. Woolfenden 1996) and 109,000 years old (Badwater) (N. E. Bader 1999). The species, or its progenitor, is estimated to have dispersed from South America between about 0.5 and 8.4 million years ago (V. V. Lia et al. 2001; R. G. Laport et al. 2012).

Selected References

None.